Published February-April 1990 in FreeNY |

Leonard Peikoff vs. Philosophy

by Barry Loberfeld

|

|

In "Fact and Value," the May 1989 Intellectual Activist encyclical in which Pope Leonard Peikoff excommunicates heretic David Kelley from the Church of Objectivism, His Holiness finally presents an ex cathedra pronouncement on "the cause of all the schisms which have plagued the Objectivist movement through the years." Contrary to what other sources might suggest, the cause, we learn, is not

differences in regard to love affairs or political strategy or proselytizing techniques or anybody's personality. The cause is fundamental and philosophical: if you grasp and accept the concept of "objectivity," in all its implications, then you accept Objectivism, you live by it and you revere Ayn Rand for defining it. If you fail fully to grasp and accept the concept, whether your failure is deliberate or otherwise, you eventually drift away from Ayn Rand's orbit, or rewrite her viewpoint or turn openly into her enemy.

Apparently having failed to grasp "objectivity," Kelley (a PhD in philosophy from Princeton University) has now become the latest "enemy" of Ayn Rand—i.e., the latest enemy of the Truth.

Given the sweeping scope of Pope Leonard's encyclical, it is paramount to address not the specifics of Kelley's alleged differences with Objectivism, but the nature of any such dissent. Significantly, the ultimate object of Peikoff's ire is Kelley's statement that Objectivism "is not a closed system." The hell you say, thunders Peikoff. "[T]he essence of the [i.e., any philosophic] system—its fundamental principles and their consequences in every branch—is laid down once and for all by the philosophy's author." A "proper philosophy," he further pontificates, "is an integrated whole, any change in any element of which would destroy the entire system." He asserts that "Objectivism does have an 'official, authorized doctrine,' but it is not a dogma. It is stated and validated objectively in Ayn Rand's works." More: This doctrine "remains unchanged and untouched in Ayn Rand's books; it is not affected by interpreters." Therefore, Peikoff concludes, Objectivism "is 'rigid,' 'narrow,' 'intolerant' and 'closed-minded.' If anyone wants to reject Ayn Rand's ideas and invent a new viewpoint, he is free to do so—but he cannot, as a matter of honesty, label his new ideas or himself 'Objectivist.'"

And now the big question is: What does it all mean? Almost unbelievably, the answer appears to be: Objectivism is What Rand Said, and that's that. The problem here is essentially one of not philosophic validity, but trademark infringement. Anyone is free to interpret, critique, and revise Ayn Rand's philosophy as he wishes—just don't market this new product as "Objectivist." Objectivism cannot be revised because What Rand Said cannot be rewritten; Objectivism thus "remains unchanged and untouched in Ayn Rand's books." Like divine revelation, Objectivism—its basic tenets "and their consequences"—has been "laid down once and for all." One cannot rewrite the Bible and then claim that it is still What God Said, and the same holds true for Objectivism's scriptures, "Atlas Shrugged and Ayn Rand's other works." And if one cannot accept these scriptures as the "'official, authorized doctrine'" of the Church, then one is compelled, "as a matter of honesty," to leave and form a new denomination.

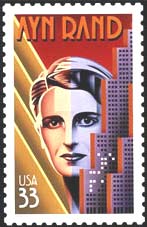

But now there arises an even bigger question, one that could be asked as easily of Pope John Paul II as of Pope Leonard: How do we know that what is stated in your scriptures is true? The historic and fundamental answer of the Christian church is: faith, which puts a neat little end to any further inquiry. It is this response, this doctrinal tenet, that establishes Christianity as a religion. But Objectivism explicitly rejects faith as a means to knowledge. For Rand, something is "true" when it has been demonstrated by reason to be consonant with the facts of reality, i.e., nature. It is this methodological foundation that establishes Objectivism as a philosophy. As "Ayn Rand's intellectual and legal heir,"[2] Leonard Peikoff is supposedly in the business of rationally defending (i.e., demonstrating) the philosophic validity of her ideas; surely the purpose of his article was not merely to protect Rand's copyrights from any potential plagiarist or bowdlerizer.

But now there arises an even bigger question, one that could be asked as easily of Pope John Paul II as of Pope Leonard: How do we know that what is stated in your scriptures is true? The historic and fundamental answer of the Christian church is: faith, which puts a neat little end to any further inquiry. It is this response, this doctrinal tenet, that establishes Christianity as a religion. But Objectivism explicitly rejects faith as a means to knowledge. For Rand, something is "true" when it has been demonstrated by reason to be consonant with the facts of reality, i.e., nature. It is this methodological foundation that establishes Objectivism as a philosophy. As "Ayn Rand's intellectual and legal heir,"[2] Leonard Peikoff is supposedly in the business of rationally defending (i.e., demonstrating) the philosophic validity of her ideas; surely the purpose of his article was not merely to protect Rand's copyrights from any potential plagiarist or bowdlerizer.

Well, Peikoff attempts a defense, but it is an embarrassing bit of "package-dealing." He himself once defined this as the "fallacy of failing to discriminate crucial differences. It consists of treating together, as parts of a single conceptual whole or 'package,' elements which differ essentially in nature, truth-status, importance or value" (Philosophy: Who Needs It, p. 30n). The first element has already been conveyed: What Rand Said is Objectivism. The second is delivered just as subtly: "The real enemy of these men"—viz., heretics such as Kelley, whom the pontiff revealingly condemns as "anti-Objectivists"—"... is reality." Peikoff couldn't have made it more explicit if he'd tried: Opposition (as determined by him) to Objectivism is opposition to reality, thus Objectivism is reality. Now A equals B, B equals C, and—ever so inexorably—A equals C: What Rand Said is reality. Evidently the map and the territory really are one and the same. And so we have Objectivism (a set of defined and presumably debatable propositions), What Rand Said (the initial arguments, "unchanged and untouched," made in favor of those propositions) and reality itself all thrown together into one fondue pot, courtesy of Leonard Peikoff.

In contrast to religion, there are two nonmystical, nondogmatic, objective means by which men can (and must) apprehend reality: science and philosophy. The first studies the physical, the second the metaphysical. In the course of men's practice of science and philosophy, conflicting schools of thought (paradigms) have arisen in each discipline. Now the facts of reality can never be rejected; they are facts. And they same holds true for science and philosophy; they are the means to the knowledge we seek. However, the disciplines' conflicting schools of thought, which cannot all be true, must be open to question and refutation. If they are not, then, as philosopher of science Karl Popper pointed out, they are unfalsifiable and therefore untenable. So, we must not allow these three distinct phenomena—facts (reality—subject), science and philosophy (the means to knowledge—method), and rival schools of thought (paradigms—theory)—to be melted in Peikoff's aforementioned pot.

Let us compare a scientific theory with a philosophic one: evolutionism and Objectivism.[3] Imagine that we have come upon a gentleman who announces himself to be "Charles Darwin's intellectual heir." In response to our question as to the precise meaning of that curious title, he tells us that he is a defender of "Charles Darwin's ideas." Meaning the theory of evolution? He nods yes. OK, then, what are his views on this ever topical subject? "Fundamentally," he begins, "I believe that once one grasps and accepts the concept of an origin of species, one then accepts The Origin of Species, commits himself to it, and reveres Charles Darwin for writing it. On the other hand, if he fails to grasp and—"

We (politely) stop him. No one, Bible Belt yahoos included, denies that species had a beginning. What we want to know is, how did he make the leap from this to evolutionism, from fact to theory, seemingly bypassing science itself, the means to knowledge?

The question does not draw an answer. Instead, his eyes narrow as he questions us: "Tell me, what are your premises? Specifically, what is your view of Charles Darwin and his achievement?" All right, what is it? First of all, we share Darwin's devotion to science: If man wishes to gain an understanding of this world, he must use his senses and his intellect, not acquiesce to mysticism and ancient scripture. Furthermore, we are impressed with a mind brilliant enough to conceive a paradigm far superior to anything produced by the "wisdom of the ages." We are committed to Darwin's theory of evolution. Consequently, we defend it against antiscientific attacks by "creationists"; on the flip side, we are interested in valid efforts to refine and develop his theory. In particular, we've taken note of the work of one biologist who has shown how the framework of evolutionism can be reinforced by revising Darwin's specific argument about ... uh, is something the matter?

We cannot help but notice that this gentleman's initial look of suspicion has rapidly mutated into one of outrage.

"What the devil are you talking about?! Nobody can 'reinforce' evolutionism by junking What Darwin Said! A scientific theory is an integrated whole, and any modification of any factor will only destroy the entire system. It is the theorist alone who lays down once and for all the fundamental principles of the theory, as well as their consequences in every branch. Yes, this makes evolutionism an authorized doctrine; however, it's not a dogma, because it is stated and validated objectively in Charles Darwin's works. Science deals with the eternal laws of the universe. Therefore a scientific theory, by the nature of the subject, is immutable. If this biologist wants to reject Charles Darwin's ideas and invent his own theory, he cannot honestly label it or himself 'evolutionist.'"

Our answer: Of course a theory must be "integrated" (coherent), and there's no straw man around disputing that. The issue is, did the theorist achieve this? A theory is a model of reality, and it is reality—not the theorist—that determines the consistency between the theory's "fundamental principles" and "their consequences in every branch." It will not do to assert that What Darwin Said has already been "validated objectively in Charles Darwin's works [i.e., What Darwin Said]." If evolutionism is not to become an unfalsifiable pseudoscience, it must remain open to scientific inquiry. (Remember, we must not collapse the distinction between science and philosophy—the means to knowledge—and any one scientific or philosophic paradigm.) A reexamination might indeed uncover a contradiction between sound "fundamental principles" and the attempted development thereof—essentially, a conflict between fact and theory. In such an instance, a dedicated man of science will amend the discordant element within evolutionism, making it consistent with the theory's fundamentals and thus with reality—irrespective of What Darwin Said. An actual example was evolutionism's eventual rejection of pangenesis, which Darwin himself accepted. To drone that evolutionism is What Darwin Said and What Darwin Said cannot be rewritten, is to create—and commit to—a dogma.

Incredibly, Leonard Peikoff has made such a commitment. "Incredibly" because, contrary to what he wrote in "Fact and Value," he too knows that it is reality—and not "the philosophy's author"—that determines the coherence of that philosophy. In The Ominous Parallels, he adduces heavyweights Aristotle and Kant as examples of a philosopher who derived a politics inconsistent with his "fundamental principles." Broadly, his claim is that Aristotelianism leads to (i.e., its premises logically imply) anti-statism, while Kantianism leads to the totalitarian state. But those familiar with What Aristotle Said and What Kant Said know that these developments do not occur within the texts themselves. Therefore, how can Peikoff contend that Kant's embrace of classical liberalism "suggests that Kant did not grasp the political implications of his own metaphysics and epistemology" (p. 33), if "the essence of the system—its fundamental principles and their consequences in every branch—is laid down once and for all by the philosophy's author"? How can he aver that "a philosopher's political views, to the extent that they contradict the essentials of his system, have little historical significance" (ibid.), if in fact every "philosophy is an integrated whole, any change in any element of which would destroy the entire system"?

Ironically (and conveniently), the area of logical implications for politics is where the internal consistency of Objectivism has been most widely questioned, viz., the market anarchism vs. limited government debate. Is it possible for a dedicated man of philosophy to demonstrate that Ayn Rand's characterization of the latter as uniquely consistent with rational individualism suggests—nay, proves—that she did not grasp the political implications of her own ethics (and, in turn, metaphysics and epistemology)? Could he then conclude that this is an exploding contradiction within Objectivism (and thus between Objectivism and reality), which precludes its validation as an "integrated whole"? And the bottom line: Would Peikoff then acknowledge market anarchism as Objectivism's politics—as the system's logical culmination—irrespective of What Rand Said? With "Fact and Value," Peikoff responds: No, because that's not What Rand Said.[4]

There's no point in beating this into the subsoil. Blind to his own blindness, Pope Leonard claims to see Kelley's cardinal sin—"subjectivism in epistemology"—in his alleged creation of the false dichotomy of "whim or dogma: either anyone is free to rewrite Objectivism as he wishes or else, through the arbitrary fiat of some authority figure, his intellectual freedom is being stifled." First off, here we have the straw man who dances, explicitly or implicitly, through every paragraph of this encyclical: the whimsical revisionist, who desires to "rewrite" What Rand Said merely to placate the rumblings of his viscera. Second, the "arbitrary fiat of some authority figure"—as a subjectivist epistemological premise—is precisely the dogma that Peikoff is sanctioning, his evident obliviousness to this notwithstanding.

Again: "Objectivism does have an 'official, authorized doctrine,' but it is not a dogma. It is stated and validated objectively in Ayn Rand's works." This is really Peikoff's most important statement, i.e., his last grasp at some measure of philosophic integrity. The reason why Objectivism cannot be questioned, much less revised, we are told, is that it all has already been proven true—factual, ergo undebatable. He is insisting that Ayn Rand drew her map accurately and so there is no need for anyone else to take a look at the territory—or even just scrutinize that map for discontinuities, ambiguities, etc. But no, the argument continues, that doesn't make Objectivism a dogma, a floating abstraction not tied by anything to reality, because philosophy—a means of objective validation—is the tie.

This line of defense presupposes what the rest of his article denies: a distinction between a theory and the philosophic method of argumentation ("experimentation," so to speak) that might validate it. Without that, Peikoff, like his What Darwin Said counterpart, decapitates himself with his own boomerang logic: "It [=Objectivism=What Rand Said] is stated and validated objectively in Ayn Rand's works [=What Rand Said=Objectivism]." Peikoff's What Rand Said approach validates nothing because a particular premise cannot be followed to its logical conclusion but is routed to a predetermined (i.e., unfalsifiable) end—as we've seen.

No, What Rand Said is not reality, any more than The Origin of Species was the origin of species—the map is not the territory (a "cliché" that’s evidently still a necessity). However, none of this is of any concern to Peikoff, for he has made no secret of his priorities: "[L]et those of us who are Objectivists at least make sure that what we are spreading is Ayn Rand's actual ideas, not some distorted hash of them." The rest of "Fact and Value" is an excruciating effort to eliminate any possible ambiguity regarding the meaning of that sentence.[5]

But what are the implications for man qua man? As the penultimate irony, Peikoff himself provides the answer, though, as is his wont, he projects it onto the David Kelleys of the world. The reader will judge to whom it (with one modification) best applies:

To such a person, intellectual discussion is a game; ideas are constructs in some academic or Platonic dimension, unrelated to this earth—which is why, to him, they are unrelated to life or to morality. Inside this sort of mind, there is not only no concept of "objective value"; there is no objective truth, either—not in regard to intellectual issues. What this sort knows is only the floating notions he happens to find [from "some authority figure."] Ideas severed from evaluation, in short, are ideas severed from (objective) cognition; i.e., from reason and reality.

Peikoff waves this as the X-ray of anyone who doesn't share his view that philosophers who argued for what eventually proved to be erroneous ideas in metaphysics and epistemology were not merely mistaken, but "wicked." If the present essay reasons from any premise, it is that it's a fundamental commitment to philosophy (and science)—and not to any one theory or school of thought—that marks a man as rational (open to argument) and therefore moral (intellectually honest). Conversely, it is with the outright rejection of philosophy or science, the abandonment of an objective means to knowledge, that we then truly have something approximating a "mental" breach of morality.

The ultimate irony is that for all of his blared commitment to What Rand Said, Peikoff can't even maintain his grasp of that. Consider a statement Ayn Rand once made to CBS correspondent Mike Wallace: "If anyone can pick a rational flaw in my philosophy, I will be delighted to acknowledge him and I will learn something from him."[6] Got that? She did not say, "Reality is immutable, so my philosophy is as well. The subject matter of philosophy is the same for men in all ages; as there are no new 'issues' to be discovered, so there is nothing new to be learned." She didn't say, "I've already committed myself on paper, so my position is now an authorized doctrine that remains unchanged and untouched." Nor did she state, "I reject the very idea of flaw-finding. A valid system of philosophy is an integrated whole, therefore my philosophy as presented to date is an integrated whole. To change any one part—to correct any 'flaw'—would be to destroy the philosophy in its entirety." And she didn't say, "How can you tell me what's 'wrong' in my philosophy? I alone decide what premises will lead to what conclusions." And she never said, "Look, if someone imagines that he's found a 'flaw' in my philosophy, he is free to reject my writings and go form his own viewpoint. The trademark 'Objectivist,' however, is retained by me. That's all that matters." She didn't condemn the could-be flaw-finder as an "enemy"—of either herself or reality. Finally, she did not pronounce Objectivism a "closed system." In short, Ayn Rand never held any of the premises that her "intellectual heir" attributes to her (and to the logical structure of Objectivism). Too obviously, there is no way to reconcile the conviction of her statement with What Peikoff Said. Equally clear is that despite whatever title he imagines Rand had bequeathed him, Leonard Peikoff has squandered the last dime of his intellectual capital.

It is interesting to read that Peikoff, until the revelations ("I finally see") of "Fact and Value," could account for challenges to his dogmatism "only psychologically, in terms of the attacker's cowardice or psychopathology." He fails to produce his qualifications for engaging in such psychologizing, which bears a striking resemblance to the Argument from Intimidation. Nevertheless, it is his own sanction of this practice, along with, more importantly, the disturbing nature of those revelations, that gives us the right to present a certified psychologist's evaluation of the young Leonard Peikoff circa 1953:

Leonard cared for nothing but philosophy—and for this, I warmed to him. But I could see almost immediately that in his consciousness there was no "objective reality," no sense of reality as such, apart from what anyone thought or believed; there were only Ayn's ideas and the ideas of his professors, and when Ayn was talking he couldn't retain the viewpoint of his professors, and when his professors were talking he couldn't retain the perspective he had learned from Ayn. I watched him, observed his struggles, tried to help him—and tried to understand how someone so intelligent could be so lacking in autonomy. Sometimes my frustration was greater than my compassion. I would say to him, "Leonard, never mind what so-and-so thinks—never mind what Ayn or I think—what do you think?"[7]

Over 35 years later, after much sound and fury, Leonard Peikoff, with "Fact and Value," has given Nathaniel Branden his answer.

[1] Douglas Den Uyl and Douglas B. Rasmussen, "The Philosophic Importance of Ayn Rand," Modern Age, Vol. 27, No. 1, Winter 1983, p. 67.

[2] Peikoff is the heir to Rand's estate; there is no evidence that she ever designated him her "intellectual heir."

[3] Before we continue, we must answer an objection pre-raised in "Fact and Value." Peikoff states that philosophy, presumably in contrast to science, "deals only with the kinds of issues [i.e., data] available to men in any era; it does not change with the growth of human knowledge...." This somehow leads him to believe that every "philosophy [i.e., each individual school of thought], by the nature of the subject, is immutable." Putting aside for now the (perhaps obvious) implications of an "immutable" theory, we will surmount this alleged disparity by focusing on the (scientific or philosophic) theorist's accuracy in assessing the data that was available to him and his coherence in integrating it—the "internal consistency" of his theory. Continental drift is a good example of a theory that gained acceptance not because of new evidence, but because of a reassessment of the old evidence, which was about a hundred years so. Consider the data Darwin himself employed: common observations of the morphology and behavior of flora and fauna. As Ludwig von Mises concluded: "What counts is not the data, but the mind that deals with them. The data that Galileo, Newton, Ricardo, Menger, and Freud made use of for their great discoveries lay at the disposal of every one of their contemporaries and of untold previous generations. Galileo was certainly not the first to observe the swinging motion of the chandelier in the cathedral at Pisa" (Epistemological Problems of Economics, p. 71).

[4] By instating "the philosophy's author" as that philosophy's authority, Peikoff has eliminated the possibility—i.e., gutted the concept—of "contradiction." Without reality as a referent, how could anyone determine whether What Smith Said in epistemology "contradicts" What Smith Said in ethics, when it's all only the same What Smith Said? With this approach, Peikoff has sacrificed objectivity for subjectivism, critical thought for personality cultism. (See Rand, "Who Is the Final Authority in Ethics?" The Voice of Reason: Essays in Objectivist Thought.)

[5] The ineluctable fate of Peikoff's crusade was observed recently by James S. Robbins. In the July 1989 issue of Liberty, he reports that a Harvard lecture by Peter Schwartz, editor and publisher of The Intellectual Activist, was a "dry rehash of Ayn Rand's thoughts read from notes ... consisting almost entirely of quotations cribbed from Ayn Rand's writings. There was nothing that a perusal of Rand's writings would not reveal. Schwartz's performance underscored the stagnation of Objectivist thinking since Rand's death." Of course: Given the premises embraced by the "Objectivist Rump," what else did he expect?